- News

- Business News

- India Business News

- It’s taxing: Selling assets and buying a new house? Beware of the tax pitfalls

Trending

This story is from January 10, 2022

It’s taxing: Selling assets and buying a new house? Beware of the tax pitfalls

MUMBAI: House property purchases have witnessed growth across India, especially in some cities like Mumbai – which saw over a lakh registrations last year. Many factors are attributed to this growth, which include lower stamp duties that were on offer in some states and softer interest rates against home loans.

Typically, the salaried masses do rely on home loans.

The sale of any asset – be it shares or an old house, results in taxable profits which in tax terminology refers to capital gains. If these assets are held for a certain period prior to their sale (for listed equity it is 12 months, for a house property it is 24 months), the resultant profit on their sale is a long-term capital gain.

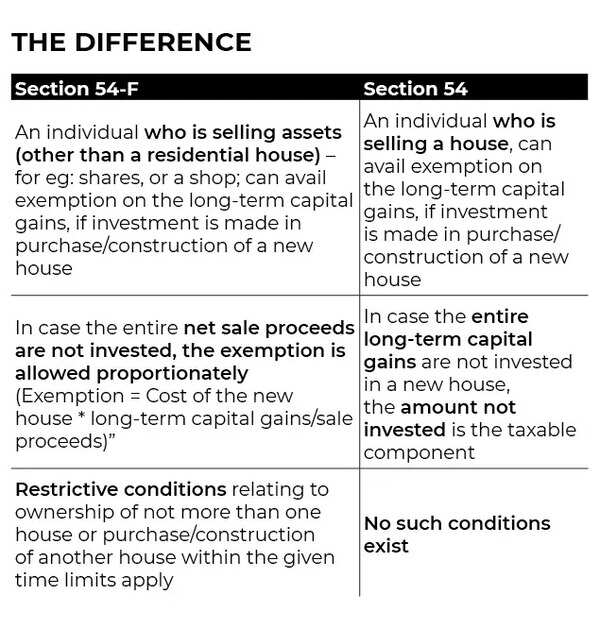

The Income-tax (I-T) Act, allows for an exemption on such long-term capital gains, if an investment is made in a new house in India, subject to certain conditions. The two sections to note in this regard are section 54-F and section 54.

When a taxpayer earns long-term capital gains from any asset (other than a house), the I-T on the gains can be saved by taking the benefit of section 54-F and investing the ‘net sale proceeds’ in a house (let’s call it a new house). Net sale proceeds denote the sale price minus expenses directly attributed to such sale.

“The quantum of exemption would depend on the amount invested in the new house. The section expects the entire net sale consideration to be invested in the new house. If the amount invested is less than the net sale consideration then the exemption would be proportional,” explains Ameet Patel, a member of the taxation committee at BCAS and partner at partner at Manohar Chowdhry & Associates.

The new house is required to be purchased either one year before the sale of the ‘original asset’ (eg: shares or commercial property that was sold and in respect of which the long-term capital gains exemption is being claimed) or two year after the sale of the original asset. Or the new house must be constructed within three years of the sale of the original asset.

There are certain restrictive conditions that need to be met. This exemption is not available if:

1.The taxpayer already owns more than one residential house (not including the new house in which the investment is being made) as on the date of sale (technical term used is transfer) of the original asset.

2.The taxpayer purchases any residential house, other than the new house, within a period of two years after the date of sale of the original asset;

3.The taxpayer constructs a residential house, other than the new house, within a period of three years after the date of sale of the original asset.

“In the latter two instances, the amount that has been claimed as an exemption earlier, is deemed to be the long-term capital gains of the year in which such violation took place,” explains Patel.

These restrictions, outlined above, do not apply when a taxpayer is investing the long-term capital gains arising on sale of a residential house, in another residential house. Thus, there is an anomaly.

“Under section 54, which provides for an exemption from long-term capital gains on sale of a residential house property, there is no restriction of having only one residential house, or of not being able to invest in more than one house (in addition to the one in respect of which the exemption is being claimed,” Patel goes on to illustrate his statement.

1.If an individual has three houses and sells one house, he can claim exemption under section 54 by investing in another residential house property (assuming conditions in this section, such as purchase or construction within the time limits have been met).

2.But, if an individual having two houses sells shares (or any other asset, other than a house) and earns long-term capital gains, he cannot claim exemption under section 54-F by investing in a residential house property. This is because of the first mentioned restrictive condition, which specifies that he cannot own more than one residential house (not including the new house in which the investment is being made) as on the date of sale of shares.

3.Similarly, if an individual has one house and sells shares and invests in a second house, he will get exemption under section 54-F (assuming conditions in this section, such as purchase or construction within the time limits have been met). But, if he buys or constructs a third house, within two/three years from the date of sale of the shares, then the exemption claimed earlier would get taxed in the year in which the third house is purchased/constructed.

“This anomaly is unfair and illogical and hopefully, we will see an amendment,” sums up Patel.

In case of purchase of a house under both sections 54-F and 54, the taxpayer can invest one year before or two years after the sale of the original asset. In case of construction, the taxpayer can construct within three years from the date of sale of the original asset.

The Chamber of Tax Consultants in their pre-budget memorandum point out that: When construction of a house is complete one year prior to the transfer of the original asset, the tax benefit should be available. Further, when the new house is being constructed post the sale of the original asset, the time period for completion of construction should be extended from three years to five years.

Typically, the salaried masses do rely on home loans.

In addition, they also have to dip into their savings and sell existing assets (be it shares or a house property).

The sale of any asset – be it shares or an old house, results in taxable profits which in tax terminology refers to capital gains. If these assets are held for a certain period prior to their sale (for listed equity it is 12 months, for a house property it is 24 months), the resultant profit on their sale is a long-term capital gain.

The Income-tax (I-T) Act, allows for an exemption on such long-term capital gains, if an investment is made in a new house in India, subject to certain conditions. The two sections to note in this regard are section 54-F and section 54.

In their pre-budget representations, professional associations such as the Bombay Chartered Accountants’ Society (BCAS) and the Chamber of Tax Consultants (CTC) have called for a change in some restrictive provisions to make life less taxing for those investing in residential properties.

Section 54-F: Restrictive conditions when an asset (other than an house) is sold and investment is made in a new house

When a taxpayer earns long-term capital gains from any asset (other than a house), the I-T on the gains can be saved by taking the benefit of section 54-F and investing the ‘net sale proceeds’ in a house (let’s call it a new house). Net sale proceeds denote the sale price minus expenses directly attributed to such sale.

“The quantum of exemption would depend on the amount invested in the new house. The section expects the entire net sale consideration to be invested in the new house. If the amount invested is less than the net sale consideration then the exemption would be proportional,” explains Ameet Patel, a member of the taxation committee at BCAS and partner at partner at Manohar Chowdhry & Associates.

Ameet Patel, a member of the taxation committee at BCAS and partner at partner at Manohar Chowdhry & Associates

The new house is required to be purchased either one year before the sale of the ‘original asset’ (eg: shares or commercial property that was sold and in respect of which the long-term capital gains exemption is being claimed) or two year after the sale of the original asset. Or the new house must be constructed within three years of the sale of the original asset.

There are certain restrictive conditions that need to be met. This exemption is not available if:

1.The taxpayer already owns more than one residential house (not including the new house in which the investment is being made) as on the date of sale (technical term used is transfer) of the original asset.

2.The taxpayer purchases any residential house, other than the new house, within a period of two years after the date of sale of the original asset;

3.The taxpayer constructs a residential house, other than the new house, within a period of three years after the date of sale of the original asset.

“In the latter two instances, the amount that has been claimed as an exemption earlier, is deemed to be the long-term capital gains of the year in which such violation took place,” explains Patel.

Need for an amendment to section 54-F:

These restrictions, outlined above, do not apply when a taxpayer is investing the long-term capital gains arising on sale of a residential house, in another residential house. Thus, there is an anomaly.

“Under section 54, which provides for an exemption from long-term capital gains on sale of a residential house property, there is no restriction of having only one residential house, or of not being able to invest in more than one house (in addition to the one in respect of which the exemption is being claimed,” Patel goes on to illustrate his statement.

Illustration:

1.If an individual has three houses and sells one house, he can claim exemption under section 54 by investing in another residential house property (assuming conditions in this section, such as purchase or construction within the time limits have been met).

2.But, if an individual having two houses sells shares (or any other asset, other than a house) and earns long-term capital gains, he cannot claim exemption under section 54-F by investing in a residential house property. This is because of the first mentioned restrictive condition, which specifies that he cannot own more than one residential house (not including the new house in which the investment is being made) as on the date of sale of shares.

3.Similarly, if an individual has one house and sells shares and invests in a second house, he will get exemption under section 54-F (assuming conditions in this section, such as purchase or construction within the time limits have been met). But, if he buys or constructs a third house, within two/three years from the date of sale of the shares, then the exemption claimed earlier would get taxed in the year in which the third house is purchased/constructed.

“This anomaly is unfair and illogical and hopefully, we will see an amendment,” sums up Patel.

Other amendments required:

In case of purchase of a house under both sections 54-F and 54, the taxpayer can invest one year before or two years after the sale of the original asset. In case of construction, the taxpayer can construct within three years from the date of sale of the original asset.

The Chamber of Tax Consultants in their pre-budget memorandum point out that: When construction of a house is complete one year prior to the transfer of the original asset, the tax benefit should be available. Further, when the new house is being constructed post the sale of the original asset, the time period for completion of construction should be extended from three years to five years.

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA