- News

- World News

- South Asia News

- How Sri Lanka’s new president moved From Marxist rebellion to mainstream

Trending

How Sri Lanka’s new president moved From Marxist rebellion to mainstream

Anura Kumara Dissanayake, a former Marxist-Leninist insurgent, has been elected as Sri Lanka's new president. His victory marks a significant shift in the nation's political landscape, traditionally dominated by dynastic families. Dissanayake aims to renegotiate IMF loan conditions to ease the burden on the poor while maintaining international support. Known by his initials AKD, Dissanayake holds more of a popular mandate than any Sri Lankan leader in recent years.

Known by his initials AKD, Dissanayake holds more of a popular mandate than any Sri Lankan leader in recent years.

In the late 1980s, Anura Kumara Dissanayake joined a Marxist-Leninist party that sought to assassinate Sri Lanka’s leaders and overthrow the government in an armed insurrection. On Sunday, he won the presidency peacefully at the ballot box.

Dissanayake, 55, has disowned the violent past of his Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna party and moved it more toward the mainstream of Sri Lankan politics.

“The elites are besides themselves at the thought that this outsider might be actually leading this country,” said Harini Amarasuriya, a lawmaker and a member of Dissanayake’s coalition. “He has been in parliament for 24 years and a political activist for about 30 years, so you can’t discount that.”

Street protesters in 2022 ousted then-president Gotabaya Rajapaksa, whose financial mismanagement contributed to bankrupting the nation and produced shortages of basic goods like food and fuel. Parliament then appointed Ranil Wickremesinghe to lead Sri Lanka into talks with the International Monetary Fund, which approved a $3 billion bailout on the condition that the country clean up its finances.

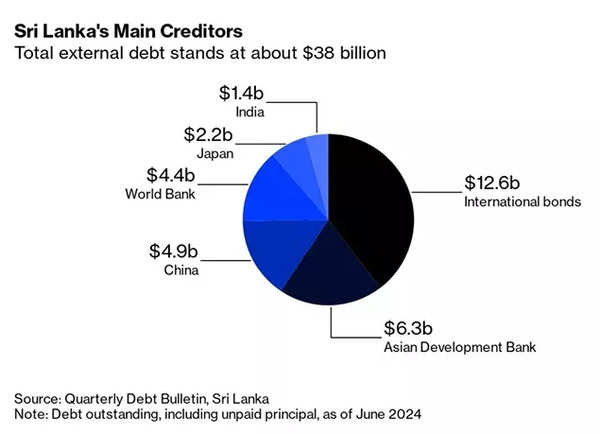

Dissanayake doesn’t want to tear the IMF deal up — a sign of how far his party has changed from the days of rebellion. But he does want to renegotiate some of the loan conditions to ease the burden on the poor. It’s also unclear if Dissanayake will follow through with the agreement struck between the previous administration and bondholders to restructure about $12.6 billion in bonds.

That uncertainty has weighed on investor sentiment. Sri Lanka’s dollar bonds due in 2027 and 2029 fell by the most in over 2 years on Monday, the first day of trading after Saturday’s election. The rupee inched higher against the dollar to 303.85, rising with stocks as investors hope for the new leader to stick with the IMF program.

During his inauguration speech in Colombo on Monday, Dissanayake acknowledged that Sri Lanka “needs international support.”

“Whatever the power divisions, we expect to act in the most advantageous way,” he said. “We should not be an isolated country. We have to go forward in the world in unity and cooperation.”

Known by his initials AKD, Dissanayake holds more of a popular mandate than any Sri Lankan leader in recent years. He emerged during the campaign as the standard bearer for the demands of the 2022 protest movement, successfully harnessing a groundswell of lingering discontent by vowing to eliminate corruption and lead with good governance.

Although his party is notionally communist, featuring a hammer-and-sickle logo on its website, Dissanayake has signaled he would balance ties between major powers — the region’s biggest strategic rivals, India and China, both major investors in Sri Lanka. In his manifesto, he pledged to re-examine international trade agreements in a bid to bolster exports, and his backers have called for greater scrutiny of investment deals with China and other nations to avoid future debt traps.

In a high-profile visit to India in February, Dissanayake held meetings with both minister of external affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar and national security advisor Ajit Doval. Two months later, a Chinese Communist party delegation visited Dissanayake’s office to discuss politics.

“When you look at his history, he has had a more nationalist stance—not pro-China or pro-India,” said Chulanee Attanayake, a researcher and sessional lecturer at Swinburne University of Technology who’s an expert in Sri Lankan foreign policy.

“Someone might assume that because they are historically a Marxist-Leninist party they will align closely with China because of their ideological similarity, but they have come a long way from being that,” she added. “In this election, they presented themselves more like a center-left party.”

A key foreign-policy test could be whether Dissanayake follows through on the previous government’s decision to lift a ban on foreign research vessels from docking in its waters. Sri Lanka had instituted the moratorium at the start of the year after the US and India complained about visits by Chinese research vessels, but later said it would lift the ban because it didn’t want to unfairly penalize China.

Dissanayake’s victory underscores the extent by which Sri Lanka’s political landscape has been upended by the crisis years. As in this election, Dissanayake in 2019 ran for president on a campaign attacking the country’s political establishment, telling a local journalist that the two leading contenders were in fact “one camp that is responsible for the socio-economic malaise that has gripped the country for the past 71 years in the post-independence era.”

“This camp resorted to the most despicable kind of acts in politics,” he said. “We joined the fray to represent the other political camp.” That year, his candidacy attracted just 3% of the vote. This year, he beat his second-place rival by more than 1.2 million votes.

Dissanayake was active in student politics with the JVP during the 1987-89 uprising against the government, which was brutally suppressed by Sri Lankan paramilitary forces. He became the party’s leader in 2014 and has since incorporated civil society leaders and academics to appeal to a broader section of society.

The party has also shifted away from its anti-capitalist roots and briefly joined coalition governments. Still, the JVP leadership is untested as administrators: The National People’s Power coalition that it leads has only three members in the 225-seat parliament.

While Sri Lankans were unhappy with the IMF deal, the economy showed signs of progress under Wickremesinghe. Inflation has slowed to low single-digits from nearly 70%, borrowing costs have fallen, growth has picked up and there were breakthroughs in debt restructuring talks.

Still, Dissanayake pointed out Monday he’s inheriting a “challenging country.” In a speech after being sworn into office, the new president said “there is a need for a good political culture that the people expect. We are ready to commit to that.”

Dissanayake, 55, has disowned the violent past of his Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna party and moved it more toward the mainstream of Sri Lankan politics.

Still, for a nation that has tended to rotate the presidency between a handful of dynastic political families, his rise to power represents an outpouring of anger among the nation’s 22 million people.

“The elites are besides themselves at the thought that this outsider might be actually leading this country,” said Harini Amarasuriya, a lawmaker and a member of Dissanayake’s coalition. “He has been in parliament for 24 years and a political activist for about 30 years, so you can’t discount that.”

Street protesters in 2022 ousted then-president Gotabaya Rajapaksa, whose financial mismanagement contributed to bankrupting the nation and produced shortages of basic goods like food and fuel. Parliament then appointed Ranil Wickremesinghe to lead Sri Lanka into talks with the International Monetary Fund, which approved a $3 billion bailout on the condition that the country clean up its finances.

Ordinary citizens ended up paying for that in the form of higher taxes and electricity bills. On Sunday, they voted in the leftist leader Dissanayake, a political outsider, in an effort to alleviate some of that pain.

Dissanayake doesn’t want to tear the IMF deal up — a sign of how far his party has changed from the days of rebellion. But he does want to renegotiate some of the loan conditions to ease the burden on the poor. It’s also unclear if Dissanayake will follow through with the agreement struck between the previous administration and bondholders to restructure about $12.6 billion in bonds.

That uncertainty has weighed on investor sentiment. Sri Lanka’s dollar bonds due in 2027 and 2029 fell by the most in over 2 years on Monday, the first day of trading after Saturday’s election. The rupee inched higher against the dollar to 303.85, rising with stocks as investors hope for the new leader to stick with the IMF program.

During his inauguration speech in Colombo on Monday, Dissanayake acknowledged that Sri Lanka “needs international support.”

“Whatever the power divisions, we expect to act in the most advantageous way,” he said. “We should not be an isolated country. We have to go forward in the world in unity and cooperation.”

Known by his initials AKD, Dissanayake holds more of a popular mandate than any Sri Lankan leader in recent years. He emerged during the campaign as the standard bearer for the demands of the 2022 protest movement, successfully harnessing a groundswell of lingering discontent by vowing to eliminate corruption and lead with good governance.

Although his party is notionally communist, featuring a hammer-and-sickle logo on its website, Dissanayake has signaled he would balance ties between major powers — the region’s biggest strategic rivals, India and China, both major investors in Sri Lanka. In his manifesto, he pledged to re-examine international trade agreements in a bid to bolster exports, and his backers have called for greater scrutiny of investment deals with China and other nations to avoid future debt traps.

In a high-profile visit to India in February, Dissanayake held meetings with both minister of external affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar and national security advisor Ajit Doval. Two months later, a Chinese Communist party delegation visited Dissanayake’s office to discuss politics.

“When you look at his history, he has had a more nationalist stance—not pro-China or pro-India,” said Chulanee Attanayake, a researcher and sessional lecturer at Swinburne University of Technology who’s an expert in Sri Lankan foreign policy.

“Someone might assume that because they are historically a Marxist-Leninist party they will align closely with China because of their ideological similarity, but they have come a long way from being that,” she added. “In this election, they presented themselves more like a center-left party.”

A key foreign-policy test could be whether Dissanayake follows through on the previous government’s decision to lift a ban on foreign research vessels from docking in its waters. Sri Lanka had instituted the moratorium at the start of the year after the US and India complained about visits by Chinese research vessels, but later said it would lift the ban because it didn’t want to unfairly penalize China.

Dissanayake’s victory underscores the extent by which Sri Lanka’s political landscape has been upended by the crisis years. As in this election, Dissanayake in 2019 ran for president on a campaign attacking the country’s political establishment, telling a local journalist that the two leading contenders were in fact “one camp that is responsible for the socio-economic malaise that has gripped the country for the past 71 years in the post-independence era.”

“This camp resorted to the most despicable kind of acts in politics,” he said. “We joined the fray to represent the other political camp.” That year, his candidacy attracted just 3% of the vote. This year, he beat his second-place rival by more than 1.2 million votes.

Dissanayake was active in student politics with the JVP during the 1987-89 uprising against the government, which was brutally suppressed by Sri Lankan paramilitary forces. He became the party’s leader in 2014 and has since incorporated civil society leaders and academics to appeal to a broader section of society.

The party has also shifted away from its anti-capitalist roots and briefly joined coalition governments. Still, the JVP leadership is untested as administrators: The National People’s Power coalition that it leads has only three members in the 225-seat parliament.

While Sri Lankans were unhappy with the IMF deal, the economy showed signs of progress under Wickremesinghe. Inflation has slowed to low single-digits from nearly 70%, borrowing costs have fallen, growth has picked up and there were breakthroughs in debt restructuring talks.

Still, Dissanayake pointed out Monday he’s inheriting a “challenging country.” In a speech after being sworn into office, the new president said “there is a need for a good political culture that the people expect. We are ready to commit to that.”

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA